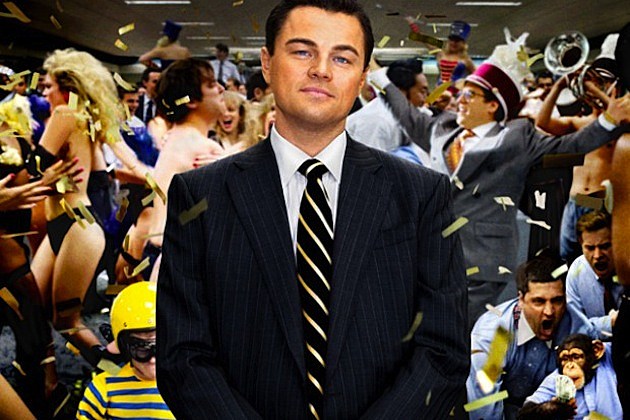

The story is of a Wall Street broker (Jordan Belford) who loses his job after Black Monday and with no other great opportunities available to him, a career in Penny Stocks is the best way forward.

From securing an IPO at Stratton Oakmont (His own brokerage firm) to the simple concept of demand and supply for a pen, this film consists of all aspects of basic economic theory to complex laws and regulation of money transferal.

Stratton Oakmont is known in the finance world as an over-the-counter brokerage house. This simply means a trade that is carried out between just two parties and their is no supervision of the exchange. Therefore this allowed Stratton Oakmont to con those involved by taking their money and not paying them back. Jason Belford wasn't a stock broker, he was a salesman. His ability to persuade the rich that he was selling them something worth buying made him a multimillionaire. The use of an illegal trading scheme, known as the 'pump and dump' allowed his firm to make money both easily and quickly. A pump and dump scheme consists of artificially inflating or 'pumping' the price of a stock to benefit those that own it. Once the price has been pumped up, owners quickly sell off the stock or 'dump' it at a huge profit causing the price to plummet. Jordan Belfort would often buy large amounts of worthless stock and then, using his flock of stockbrokers at Stratton Oakmont, spread rumors and positive statements about the company. This caused the price of the stock to rise rapidly. Once the stock reached record highs, he and his associates would sell it off, causing the price to reach record lows.

The ability of making money effortlessly didn't last forever. Joseph Borg, a financial administrator who served for the securities comissioner of Alabama, investigated the firm from 1994 due to overwhelming number of complaints regarding Stratton Oakmont. Following an investigation into their illegal trading schemes they were taken to court and prosecuted soon after. Belford spent 22 months in prison and was ordered to pay over $100 million in restitution to his victims (which he has apparently failed to do). As the film depicts, he became a motivational speaker after leaving prison; at the seminar in the movie, DiCaprio as Jordan is introduced by the real Jordan Belfort.

As well as the record breaking number of F-bombs being dropped, the film contains numerous scenes of nude women and prostitutes. Drugs are the norm throughout and being sober is a rarity. For those wanting to work in the city, take a leaf out of Jordan's book.

(Sorry to those of you who thought this may have been about the book; Sex, Drugs and Economics. Sadly, it is not.)